Image found on Storyblocks

Calls are growing for companies to become sustainable. The expectation: companies must help shift the global economy to reduce inequality, rapidly decarbonize, preserve biodiversity, and eliminate waste. Creating value for company stakeholders is often a core part of these calls. In 2019, America’s Business Roundtable declared in The Purpose of the Corporation1 that companies must “promote an economy that serves all Americans” which was hailed by many as a win for corporate sustainability. Many other voices have joined the chorus of stakeholder capitalism, from big consulting2 to international organisations,3 and companies big4 and small.

As a result, your company has likely also become more responsive to the expectations and needs of a broad range of stakeholder groups. But you may be questioning if this is enough to ensure a sustainable future. And you would have good reason to do so.

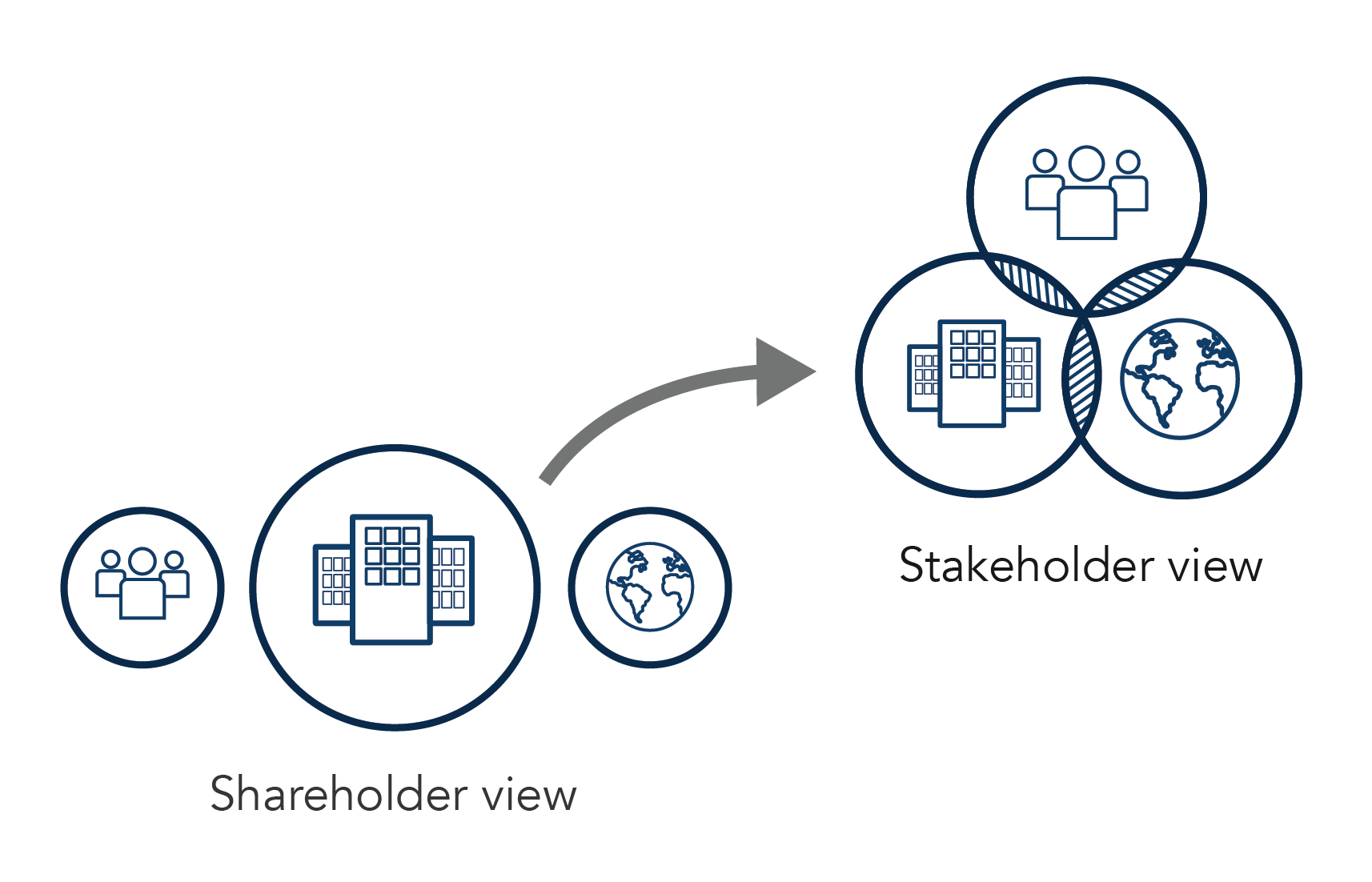

The shift to stakeholder value

An increased focus on employees, suppliers, communities, customers, and other stakeholder groups represents an overdue rejection of shareholder capitalism; a perspective on business that became prominent in the 1970s and has influenced corporate operations and decision-making ever since. At its core, a stakeholder (vs shareholder) view discards the notion that the corporation exists exclusively to create value for its shareholders (including its leadership) while meeting the demands of the market. This view also rejects the idea that the impacts caused in that process are not the company’s concern, unless legally required.

A stakeholder view helps companies consider where their interests overlap with those of society and the environment.

Adopting a stakeholder perspective helps companies better understand their adverse and positive impacts on thriving societies and a healthy planet. The idea is that companies assess where their interests overlap with those of society and of the environment (as in the diagram above). And in those areas of mutual benefit, companies then can find so-called shared value opportunities,5 where their business activities also create positive social and/or environmental outcomes.

Many companies are now seeking out such win-win initiatives. “Doing well by doing good,” so to speak. This has been a step forward for corporate sustainability. No doubt about it.

But is creating shared value enough to support the transition to a more regenerative economy and a sustainable future? And how do you even know what doing enough looks like?

The limitations of stakeholder capitalism

At the Embedding Project, we have interviewed hundreds of senior leaders and worked with dozens of leading global companies for over a decade to help them factor the needs of their environmental, social, and economic context into their core strategy and goal-setting processes. From these engagements, our research, and the events of the last few years, it has become clear that a stakeholder view represents a positive shift but does not adequately enable companies to address the disruptive risk that is posed by the declining resilience of socio-ecological systems across the world.

Here are some of the reasons why:

1. Positive contributions here don’t offset adverse impacts there

Once your company realizes that stakeholder groups are negatively affected by its actions, your response may be to make contributions or support initiatives aimed at benefiting those groups. The basic version is a free pizza lunch for a team that has consistently worked overtime. Or, after realising that your highly paid employees contribute to income inequality and housing affordability in regions where you operate, you may decide support affordable housing or shelters for those without homes. Or to encourage the acceptance of, say, a new energy-intense data center, you may promise local jobs or local supplier opportunities.

The idea there is that the positive contribution balances out (some of) the adverse impacts. Much like the narrative that has evolved around the idea of carbon offsets.

But as a society we are realizing that carbon offsets are an unscalable and a temporary solution at best. The positive impact your company has in one area does not actually offset the adverse impacts you have elsewhere. A free pizza lunch may boost morale, but it doesn’t erase the additional stress and fatigue.

And so, shared value initiatives cannot just make up for other ways your company may erode community or ecosystem resilience. And often, they work against long-term sustainability, but more on that later.

2. Companies need to do more than balance interests

Your company, like all companies, has limited resources and you need to make strategic decisions about how you use those resources. Realistically, your company can only act on a limited set of expectations. So, responding to the expectations and needs of all your stakeholders quickly becomes an exercise in balancing various interests. Priority often goes to meeting expectations most aligned with achieving company objectives and to responding to those stakeholders with the most influence, which can entrench social inequities.

As a result, all too often, navigating these competing demands leads companies to default to legal obligations and meeting regulatory requirements (though some companies still file fines for violations under ‘the cost of doing business’).

Business continuity is the ultimate goal. And if stakeholder needs are not contributing to that goal, they risk becoming deprioritized during challenging times. If your company is like most, it goes through cycles. And perhaps its priorities shift. This happens in many organisations, despite the best intentions. Case in point: an initial assessment6 in 2020 of the outcomes of the Business Roundtable pledge showed limited follow-through on the part of the pledging companies.

These tensions arise even when supporting a more sustainable future is very much part of your company’s brand identity. Because the challenge with basing your strategy on balancing interests is that these interests may be conflicting. And so, you may find your company in the position of promoting recycling while simultaneously fighting the right to repair7 or promoting your sustainability efforts while also trying to dilute ESG disclosure requirements.8 The apparent contradictions of these trade-offs are often the result of companies like yours failing to recognize that supporting the resilience of socio-ecological systems needs to be factored into your core strategy.

3. Meeting stakeholder expectations may not yield long-term sustainability

A stakeholder lens can certainly help your company to see that it has interests in common with its stakeholders.

But look again: in the overlapping circles of the stakeholder view, vast areas of socio-ecological resilience still reside outside of business interests. This means that crucial sustainability challenges risk being overlooked. Or your company may end up engaging in well-intentioned ‘win-win’ initiatives that often don’t address the underlying issues (or worse yet, end up with unintended consequences).

And equally challenging: the interests of your stakeholders don’t always align with the needs of the environment or society more broadly. For example, some communities’ need for economic resilience may drive them to pursue unsustainable companies or projects in an effort to secure much-needed local jobs. And understandably so. But this illustrates the complexity. If your company pursues shared value in support of ‘business as usual,’ these efforts do little to promote the shift to a more regenerative economy.

Even if your company has shared value initiatives that are explicitly intended to contribute to sustainability and wellbeing, it may in fact erode long-term sustainability. Remember TOMS shoes, which unintentionally undermined local footwear markets with its one-for-one model that donated a pair of shoes for each purchased pair? And you can no doubt think of other initiatives, perhaps at your own organization, that at best served to maintain the status quo (the system that caused the challenge to begin with) or, worse, have had unintended adverse consequences for ecosystems or communities.

In fact, if your company takes an incremental approach to sustainability, if it aims to meet the needs of its stakeholders and the environment step by step, its contributions to long-term sustainability are inherently limited. This article9 hit the nail on the head: a company aiming to be “more sustainable than before” is not the same as a company being as sustainable as it needs to be. The author calls this “enough sustainability in time,” that ensures we don’t irreparably damage the social and natural systems on which we depend. The shift to a regenerative economy needs companies to do exactly that.

4. A stakeholder focus risks ignoring the bigger systems at play

You’ve no doubt read between the lines by now. A focus on stakeholders alone obscures the fact that companies rely on more than positive, beneficial stakeholder relations and shared value initiatives for their long-term business success.

The challenges we face globally, regionally, and locally are mostly systemic in nature. Solving them will require more than bilateral engagement between companies and stakeholder groups. It calls for multi-stakeholder, long-term, collaborative efforts, at the systems level.

Bees are an interesting example. As companies learned about the challenges facing honeybees, many launched efforts to create habitat for the protection of these vital insects. But it turns out that these well-meaning initiatives have been destabilizing natural ecosystems by competing with native bee species and other crucial pollinators.10 A systems approach might have foreseen this.

What does this mean?

So, stakeholder capitalism has some concerning limitations. What does that mean for your company?

To be clear: it does not mean that you should not consider the needs and expectations of your stakeholders or that you should deprioritize these demands. Fostering transparent, trusted relationships with your stakeholders will still be crucial to your company’s long-term success: integrating the needs and expectations of these groups into core strategy can help your company to seize opportunities for positive impact and manage enterprise risk.

It also doesn’t mean that all shared value initiatives are missed opportunities to do better. They may be. But they aren’t always.

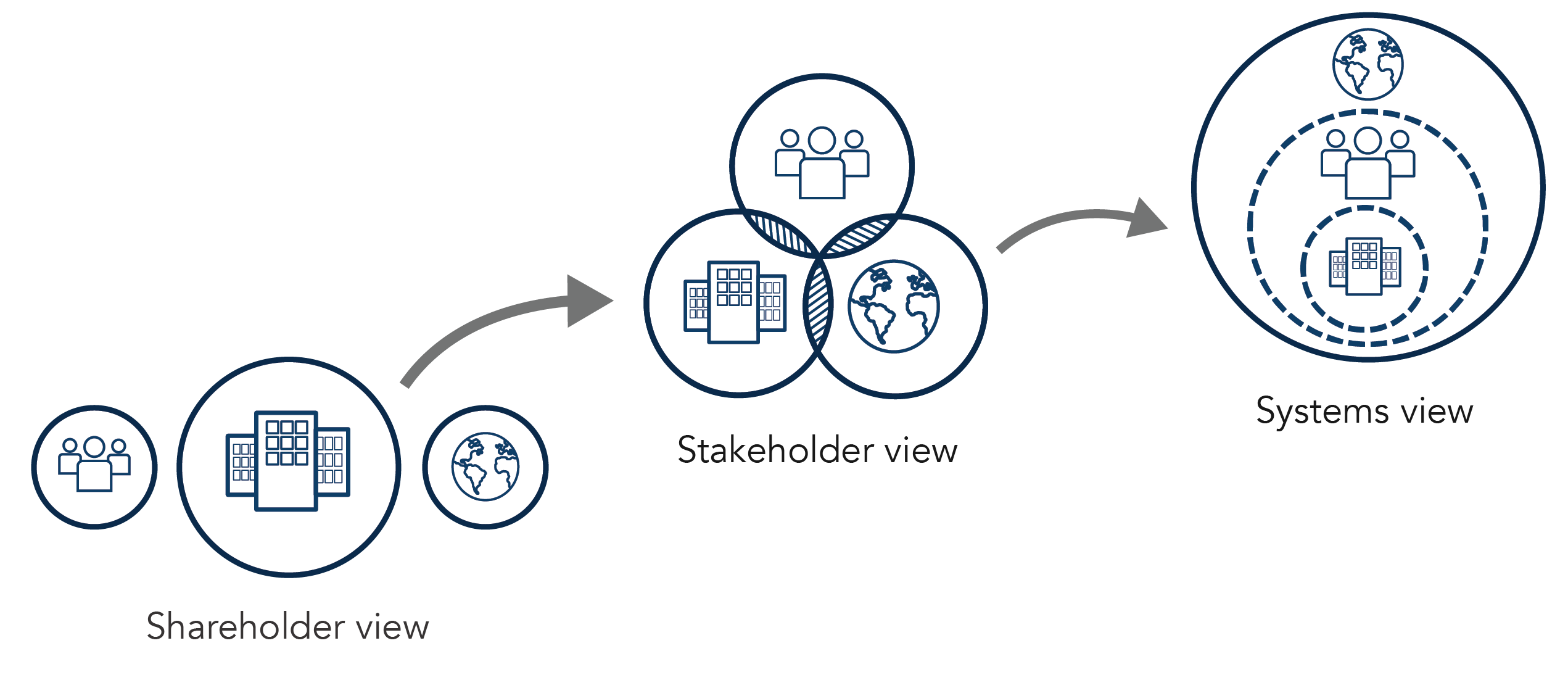

But what it does mean is that being a stakeholder-focused business is not synonymous with being a sustainable business. To be as sustainable as it needs to be, your company must not only recognize and internalize that it is part of broader systems, but also that its long-term success relies on the resilience of these social and ecosystems around it. And act accordingly.

Source: Embedding Project

Companies are part of the broader social and ecosystems systems around them and companies’ long-term success relies on the resilience of these systems.

A good place to start is for your company to determine what it looks like to do its part11 to support systems resilience. This is not an easy task. The world is complex: a quick brainstorming session won’t do it. But if your company is ready to explore what is needed, there are resources to get you started. Be sure to read this guide on setting priorities and goals aligned with systems resilience.12

And know that you’re not alone on this journey. More and more companies are now recognizing the need to think from a systems value perspective. They have started to view their operations and their broader value chains as part of a nested system, bounded by, and embedded within, the environmental, social, and economic systems in which they operate. Not a stakeholder view, but a systems view.

Your company can adopt a systems perspective too. Discover our curated resources on thinking systemically to learn more.

Image found on Storyblocks

Footnotes

1 ”Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote 'An Economy That Serves All Americans’.” Business Roundtable, 19 Aug. 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

2 Hunt, Vivian, et al. “The Case for Stakeholder Capitalism.” McKinsey & Company, 18 Nov. 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-case-for-stakeholder-capitalism.

3 “Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation.” World Economic Forum, 22 Sept. 2020, https://www.weforum.org/reports/measuring-stakeholder-capitalism-towards-common-metrics-and-consistent-reporting-of-sustainable-value-creation.

4 Benioff, Marc. “We Need a New Capitalism.” The New York Times, 14 Oct. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/14/opinion/benioff-salesforce-capitalism.html.

5 Kramer, Mark R. and Marc Pfitzer . “The Ecosystem of Shared Value.” Harvard Business Review, 6 Sept. 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-ecosystem-of-shared-value.

6 Goodman, Peter S. “Stakeholder Capitalism Gets a Report Card. It's Not Good.” The New York Times, 22 Sept. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/22/business/business-roudtable-stakeholder-capitalism.html.

7 Bergen, Mark. “Microsoft and Apple Wage War on Gadget Right-to-Repair Laws.” Bloomberg, 20 May 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-20/microsoft-and-apple-wage-war-on-gadget-right-to-repair-laws.

8 Nauman, Billy. “Top Tech Groups Try to Dilute ESG Disclosure Rules.” Financial Times, 20 June 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/894aeb77-8bc4-4c05-a491-7cfb56e7935e.

9 Austin, Duncan. “From Win-Win to Net Zero: Would the Real Sustainability Please Stand up?” Responsible Investor, 20 May 2021, https://www.responsible-investor.com/articles/from-win-win-to-net-zero-would-the-real-sustainability-please-stand-up.

10 McAfee, Alison. “The Problem with Honey Bees.” Scientific American, 4 Nov. 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-with-honey-bees/.

11 Toews, Brandon. “Companies Need to Take a Stand. Here's How to Do It Right.” Embedding Project, 20 Apr. 2021, https://embeddingproject.org/blog/how-to-create-a-sustainability-position-statement.

12 Bertels, Stephanie, and Rylan Dobson. “Embedded Strategies for the Sustainability Transition” Embedding Project, 1 Jan. 2020, https://embeddingproject.org/resources/embedded-strategies-for-the-sustainability-transition.