Materiality Assessments: Why It’s Time for a New Approach

Share this post on:LinkedIn

Image by Tony Campbell on Shutterstock

Is it time to revamp your company’s approach to materiality? Yep, likely it is.

Materiality assessments take significant time and resources. Done well, they should improve the quality and relevance of your disclosures and ideally, clarify where your company needs to act and inform your core business strategy. Unfortunately, most materiality assessments haven’t lived up to that promise. In this blog post, we reflect on how we got here and why the corporate sustainability materiality assessment process is in desperate need of an overhaul.

In our next blog (Part 2), we’ll share a new approach to corporate sustainability materiality assessment that we have been piloting and developing over a period of 5 years. Our approach is more comprehensive, grounded in context and impacts, brings useful insights into your corporate strategy process, and will help your company prioritise where to act to do its part to support sustainability.

Why materiality processes need a revamp

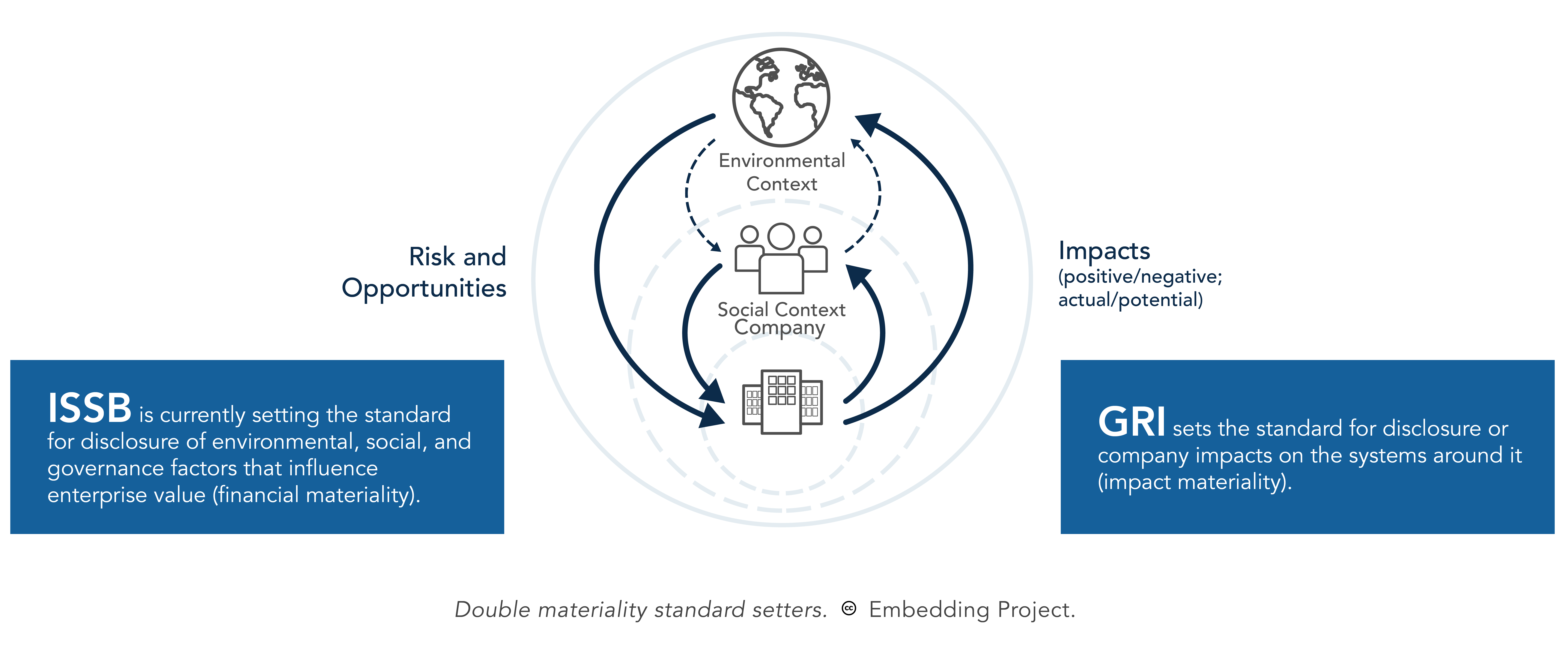

Heading into reporting season this year, many companies are looking for guidance on how to adapt and revitalise their materiality process to address double materiality: the impacts of environmental, social, and governance issues (ESG) on companies (financial materiality) and the impacts of companies on people and the planet (impact materiality). The concept of double materiality is gaining traction, having been enshrined in the EU's new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

The ISSB (International Sustainability Standards Board - overseen by the IFRS Foundation, the body that develops the accounting standards used today in more than 140 countries outside of the US) has released the first two global standards in June 2023. IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 prescribe the disclosure of environmental, social, and governance factors that influence enterprise value (financial materiality). The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) sets the standard for disclosure of a company’s impacts on the systems around it (impact materiality).

Granted, uptake of double materiality has been slower in the US where the GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) are still anchored in single (financial) materiality. But US companies that report in accordance with GRI are still going to need to make a shift towards determining materiality based on an understanding of actual and potential impacts.

The updated GRI Universal Standards took effect January 1, 2023 and they define material topics as those that “represent the organization’s most significant impacts on the economy, environment, and people, including impacts on their human rights”.

The updated standards place a renewed emphasis on both context and impact. When it comes to materiality, companies are now instructed to: understand your company’s environmental and social context; identify actual and potential impacts on people and the planet; assess the significance of the impacts (instead of importance and significance to stakeholders); and prioritise on that basis.

…and that has caused a lot of handwringing.

Why context and impacts are key to materiality

Though it may feel like a very big change for some, the focus on context and impacts is not new. It’s just that for 20 years, most materiality processes have managed to totally side-step talking about them.

Let’s start with a little trip down memory lane and note that understanding your context and impacts have always been the goal. For instance, the 2002 version of the GRI guidelines (that’s more than 20 years, by the way) notes that “particular care should be taken to match the scope of the report with the economic, environmental, and social “footprint” of the organisation (i.e., the full extent of its economic, environmental, and social impacts.” At the time, this already included direct and indirect impacts, positive or negative. And, back in 2002, they also noted the importance of the core principle of context, which involves assessing performance “in the context of the limits and demands placed on environmental or social resources at the sectoral, local, regional or global level.”

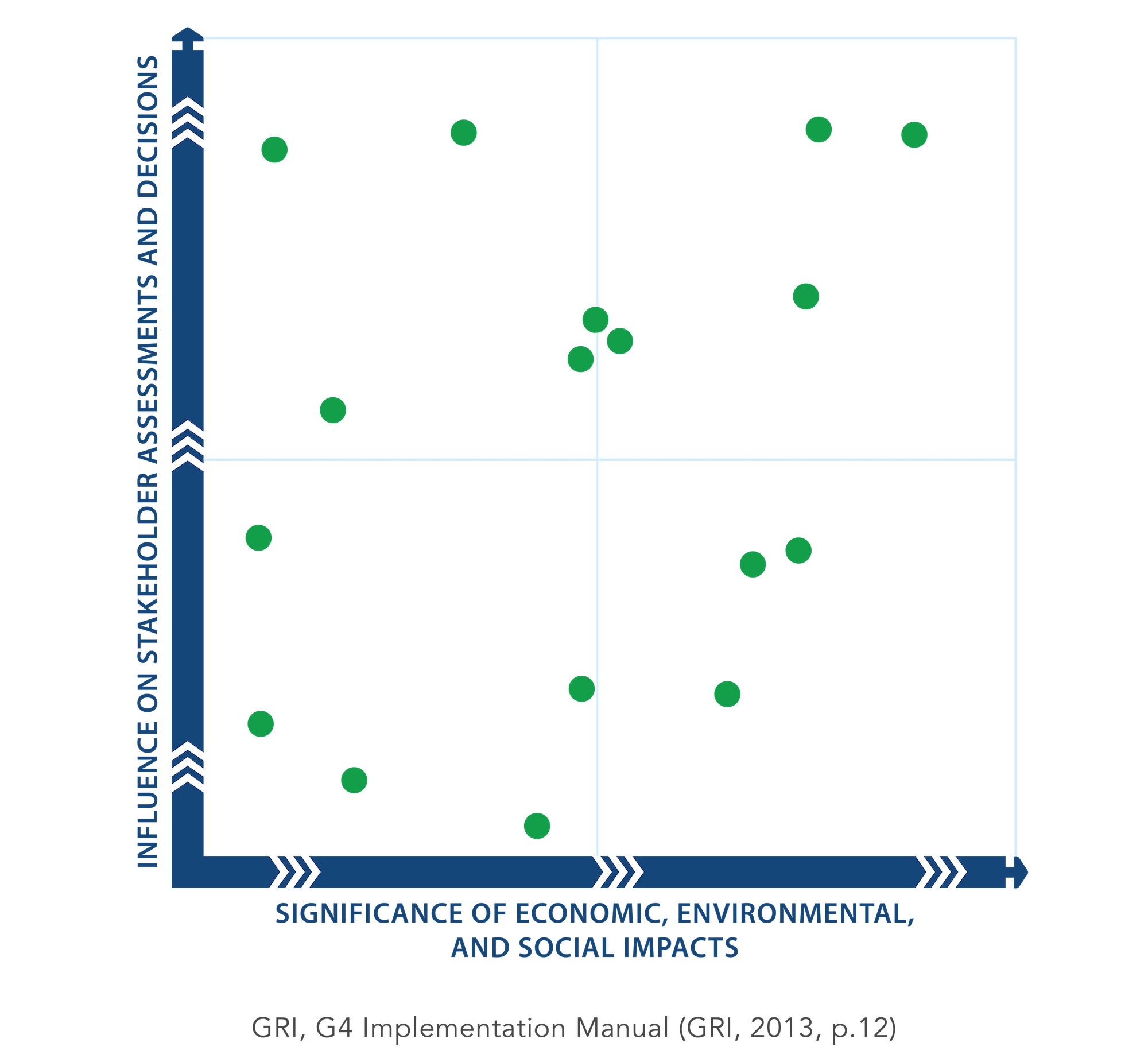

In 2006, the GRI G3 standards formalised the principle of materiality, which they defined as “…topics and indicators that reflect the organization’s significant economic, environmental, and social impacts, or that would substantively influence the assessments and decisions of stakeholders." As part of that definition, GRI included a matrix and noted that the most material issues would be those where there are the most significant impacts on the systems around you (either directly or indirectly) and where these impacts would be important to stakeholder assessments and decisions.

But determining the significance of economic, environmental, and social impacts was (and is) hard. Remember, this was back in 2006, a time when the methods of social and environmental impact assessments were still very much being developed and were primarily being undertaken by large resource companies.

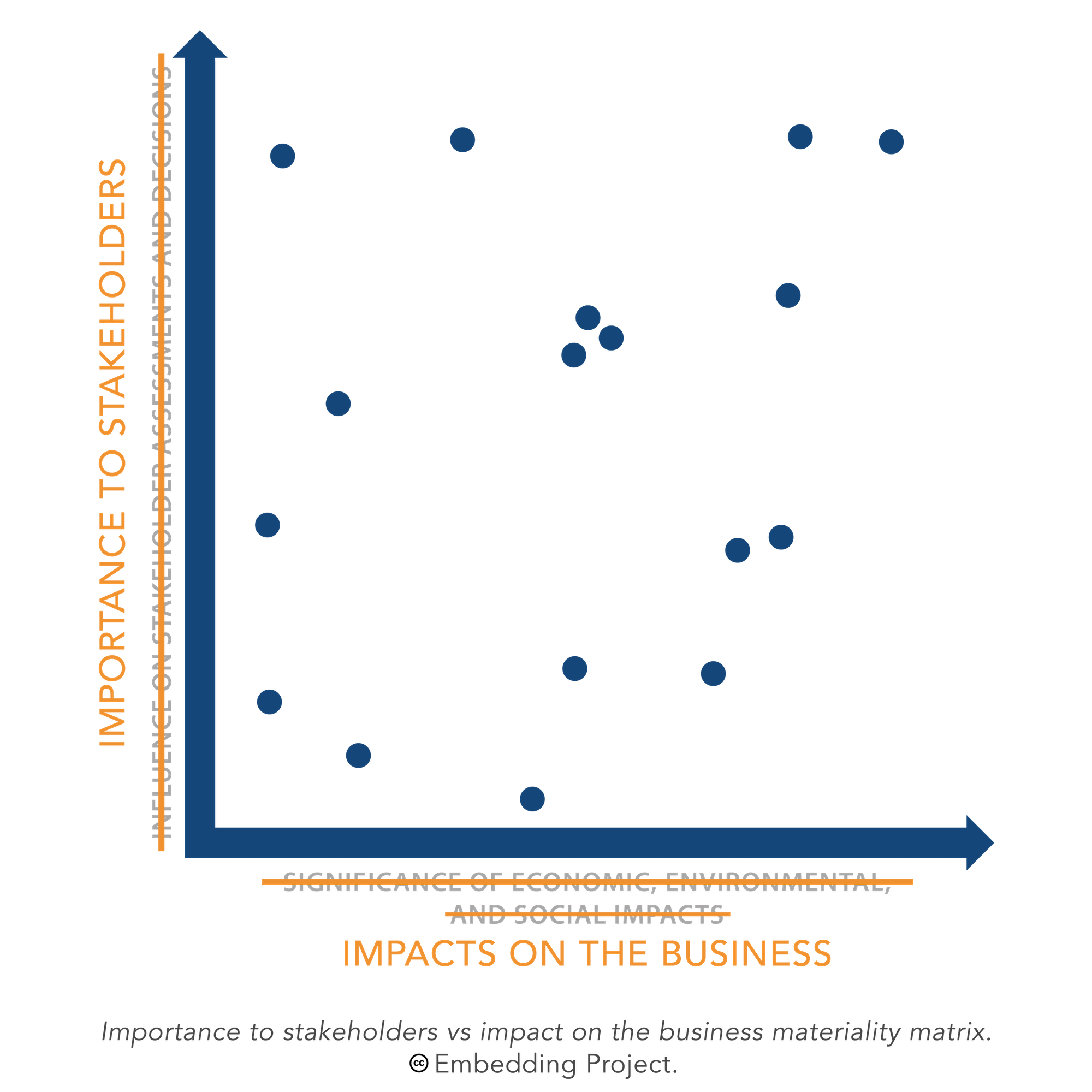

But fear not, a quick sleight of hand and renaming of the axes solves the problem: impacts on the underlying systems around you gets swapped for impact on the business and influence on decisions becomes importance to stakeholders (now it’s just an opinion or a demand). Not to point fingers, but one of the first reports that we found to take this approach was Ford’s 2004-2005 sustainability report. If you find an earlier one, do let us know and we’ll update our finger-pointing.

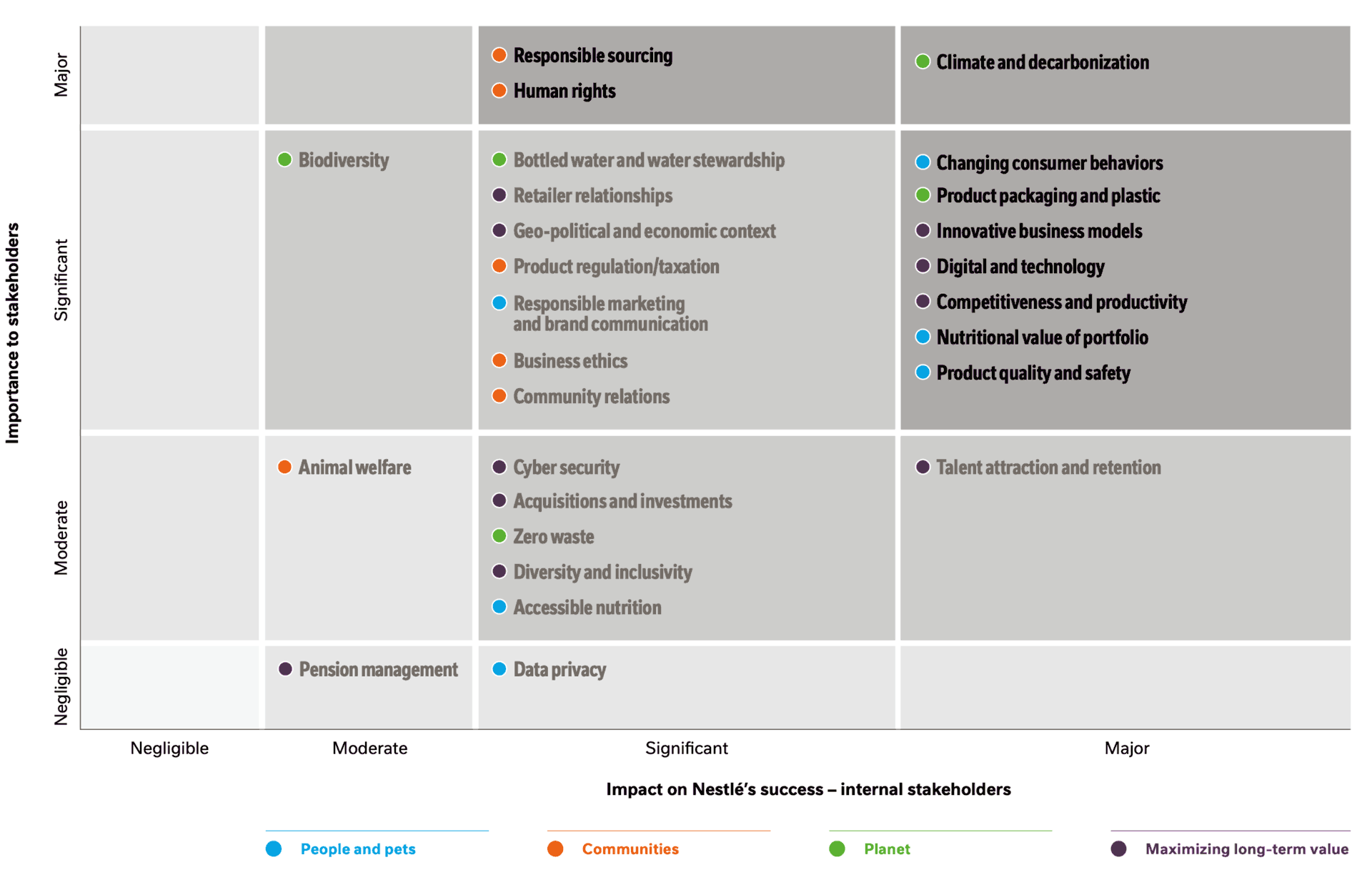

Next thing we know, we have almost two decades of materiality assessments that take a decidedly different approach – us versus them. Go ahead, open almost any sustainability report and we bet you will find a materiality matrix full of issues plotted as dots based on their importance to stakeholders and their potential to impact the business. Likely those issues were identified and ranked using a questionnaire with a pre-set list of issues sent out to stakeholders asking them to rate their importance to them. How do we know? We are asked to participate in dozens of them every year.

A typical importance to stakeholders – impact on the business materiality matrix.

Here’s the problem: materiality assessments that focus on perceived importance very often fail to identify emerging sustainability issues and business risks, fail to direct attention towards your company’s biggest impacts and greatest opportunities to contribute to positive systems change, and as a result, struggle to meaningfully inform business strategy. In what other part of the strategy process do we look out the window and ask who is carrying the largest placard?

It's time for a change. That’s why we are excited about the renewed attention to materiality that double materiality and the updated GRI standards have spurred. Yet, despite the momentum around double materiality and impact, many companies (and the consultants who advise them) are struggling to adapt their approach to materiality.

So, what would a more meaningful approach to understanding the materiality of sustainability issues look like? Glad you asked.

The reinvention of materiality

First, the issues that are of most strategic relevance to a company cannot be adequately assessed without understanding the state, needs, and limits of the social and environmental systems upon which that company depends. That means context needs to underpin your materiality process.

Companies rely to a great extent on the healthy functioning of the social and environmental systems around them. Changes or disruptions to those systems, such as from disease outbreaks (think: COVID-19), climate change, biodiversity loss, or human deprivation and rights abuses, can deeply affect the short-to-medium-term performance and even the long-term resilience of companies. Because of this, the sustainability issues that are most material to a company and its stakeholders depend on how that company (and its value chain) affects these issues and how those issues, in turn, can affect the company and its ability to achieve its objectives.

In other words, understanding context is key to understanding company impacts and company impacts are the key to meaningfully assessing non-financial materiality (and ultimately, financial materiality).

Second, focus on the process. This isn’t just about demonstrating you have consulted with stakeholders by sending out a questionnaire. It’s not just about coming up with a rank ordered list of material topics, the key to disclosure is explaining the process that was used to determine these topics. You need to show that you have engaged in a comprehensive process to identify and evaluate actual and potential impacts and that you have a rigorous process to prioritise among them.

OK, but how do I do that, you may ask? Luckily, the Embedding Project, working with several of our partner companies over a period of 5 years, has been developing, piloting, and refining a new approach to corporate sustainability materiality. Stay tuned for Part 2 of this blog, where we will share this new approach to materiality – one that is more comprehensive and rigorous, grounded in context and impacts, brings useful insights to your corporate strategy process, and will help your company prioritise where to act to do its part to support sustainability. Oh, and yes, it meets the expectations of ISSB/SASB and GRI.

Further Resources

Our Scan Guide provides a comprehensive list of sustainability issues to help organizations identify which issues are most relevant to them and our Issue Snapshots tool is a curated selection of resources on key sustainability issues.

To understand more about how materiality processes need to shift and what that could look like, check out our Embedded Strategies Guide.

Or to learn more about context and social and environmental thresholds, take a look at the Planetary Boundaries framework, Kate Raworth’s Doughnut of Planetary Boundaries and Social Foundations, the Future-Fit Business Benchmark, and the evolving work of the Global Thresholds and Allocations Council.

For an interesting alternative approach to materiality that focuses on what a company does and how this affects the world take a look at this evolving work on matereality.

Image by Tony Campbell on Shutterstock.