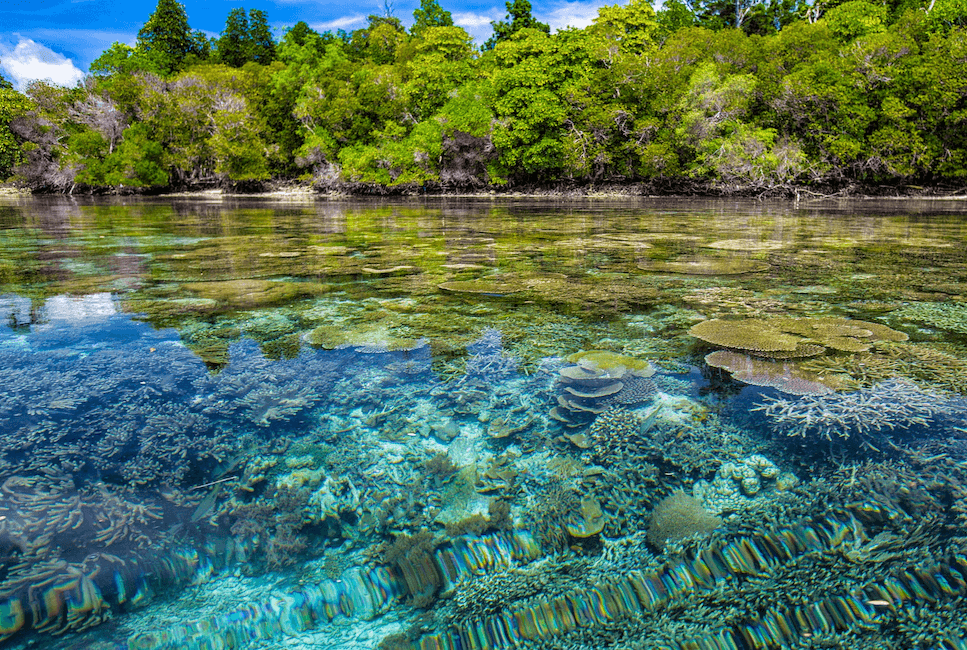

Image by Kanenori on Pixabay

In our work with companies across the world we’ve heard time and again that systems thinking is a crucial sustainability capability. Companies that use systems thinking are better able to identify the variables relevant to their decisions, anticipate unintended consequences, recognize thresholds, identify leverage points, and design collaborative responses to system challenges.

That said, you and your team may find yourselves facing some hard-to-overcome hurdles when implementing your systems thinking approach. This blog post identifies common challenges that companies encounter when they use systems thinking. And, most importantly, suggestions on how to get unstuck.

Challenge 1: Reframing the System

Many executives think in systems already, even if implicitly. But their experience, training, and context have often narrowed their focus on particular systems and corresponding system boundaries, such as industry dynamics or the organisation’s financial system. As an effective change agent, your opportunity is to make use of these existing system thinking skills, but to broaden the type and scale of systems that come into view. As one executive remarked, “Once we begin to see that the systems we need to manage are broader than we first thought, we can’t ‘unsee’ this.” Some ideas on how you might go about this are included in our Change Agent resources, such as our guide on supporting your CEO.

Challenge 2: Siloed Teams

Your company may find it difficult to apply systems thinking in its corporate decision-making because different departments or groups continue to work in silos. Decisions that don’t include relevant internal (or external) perspectives can fail to achieve your company’s desired outcomes. They may be missing a broader understanding of the variables at play or may lead to unintended consequences for your organization and/or for the social and environmental systems in which you operate.

To move beyond silos, it can help to do some internal capability building. Providing managers with encouragement and training on systems thinking can help motivate the creation of better communication between teams and departments. In turn, as people engage across departmental boundaries, they get better at seeing the bigger picture and therefore at systems thinking: a positive feedback loop!

Challenge 3: Spaghetti Soup

Exploring systems often gives rise to the identification of many elements and inter-relationships, and the resulting causal-loop diagrams can quickly turn into “spaghetti soup.” All this complexity can be overwhelming to people. At the same time, it’s difficult to streamline a systems analysis without losing the essential strengths of systems thinking.

One response to this conundrum is to demonstrate to peers and executives that you have done the full analysis and considered the inherent complexity of the system, but then to home in on those system elements that are essential for decision-making. In this way, your colleagues can appreciate how you have come to your recommendations, without getting lost in the spaghetti soup.

Additionally, there are other systems thinking frameworks that can help, such as what we call the “onion model.” In this approach, you zoom in on a particular part of the system that is of most importance to you and then zoom out by considering successive layers of the system. For instance, if you are trying to figure out how to respond to food insecurity in a given community, you might focus on the most vulnerable children in that community. You can then attend to successive layers of the system, such as the household, local food markets, and so on. Considering the various spatial and temporal layers of a system like this can provide an intuitive structure, so it can be a useful complement to causal loop mapping.

Challenge 4: Paralysis

Another, related risk is that systems thinking can overwhelm people because it makes them feel like there is no way to start to address complex social-ecological problems. If there are so many elements and interdependencies at play, where do we even begin to make a difference?

To avoid this kind of paralysis, it is important to emphasize that systems thinking is not only helpful to better understand the complexity of a system, but also to identify possible interventions in the system. There are two key aspects to this: leverage points and collaboration. Leverage points are those parts of a system, where a well-targeted intervention is most likely to bring about the desired changes in the broader system. Designing and implementing such interventions often requires collaboration with other actors. Examples of these leverage points can be found in our guide on partnering for community resilience.

Systems thinking does highlight complexity – but it also offers tools for tangible action in the face of this complexity.

Challenge 5: Grappling with Uncertainty

Systems thinking forces us to grapple with uncertainty. As diverse system elements interact, they give rise to non-linear dynamics including thresholds. These result in often significant inherent uncertainty that cannot be wished away: a type of uncertainty that defies quantitative risk assessment, called Knightian uncertainty.

This creates two kinds of challenges. The first is that some colleagues may look to you for definitive answers, based on your system analysis, and they might see a lack of certainty as a weakness of your analysis. Such colleagues need firm but gentle persuasion on why and how uncertainty is an inherent characteristic of complex systems. Unwillingness to grapple with uncertainty all too often leads to rash decisions with unintended consequences.

The second challenge is that some colleagues may see in such uncertainty a reason for inaction. In response, consider emphasizing how your system analysis points to the existence of specific risks and hazards– and even if they cannot be quantified, such risks still warrant mitigating actions.

To learn more about thinking systemically, discover our curated resources.